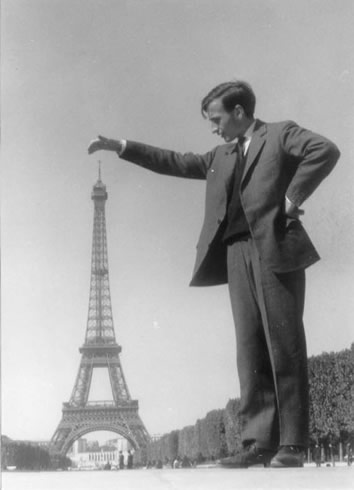

This is Roger Federer. Currently he is 3rd in the ATP World rankings. His record of 16 Grand Slam (GS) titles, including 10 consecutively, along with 23 finals appearances has him regarded by many as The Greatest Tennis Player ever. The other man is Paul Annacone. His highest ATP ranking was 12. In 7 years on the ATP Tour he never progressed further than a Grand Slam quarter fin al. Paul Annacone is Roger Federer’s coach. Previously he had coached a little known Californian by the name of Panayiotis Sampras. Most people called him “Pete”.

al. Paul Annacone is Roger Federer’s coach. Previously he had coached a little known Californian by the name of Panayiotis Sampras. Most people called him “Pete”.

It is clear in tennis that leading players continue to excel not because of personal insight and innate talent but because of the input of coaches such as Annacone who can observe and guide their charges to even greater performance that they themselves may no longer or ever have been able to achieve. The suggestion that a player as good as Federer can improve or has a coach would surprise few. Many however would be uncomfortable with the knowledge that technical specialists such as Consultant Surgeons aren’t as good as they possibly can be and don’t have coaches to help them achieve optimal performance. What is not suggested by either of these facts is that the performance currently achieved is unacceptable, merely that it is not not exemplary; Federer wants more Grand Slams and surgeons want to excel.

I raised this In my previous post . It may be uncomfortable to hear of shortcomings in performance, difficult to action and even harder to change consistently but if that improvement is possible for Federer or for a surgeon surely that achievement is of greater import than the disquiet, arrogance or ignorance resisting it. Personally, I’m interested to look at my practice both within the theatre and outwith to consider opportunities to improve. I’m sure the same could be applied to any clinician and even manager. Who wouldn’t want to be as good as they possibly can be?